TOP STORIES

From the Archives

Exploring how yesterday’s history shapes today’s headlines

Bass & Beyond

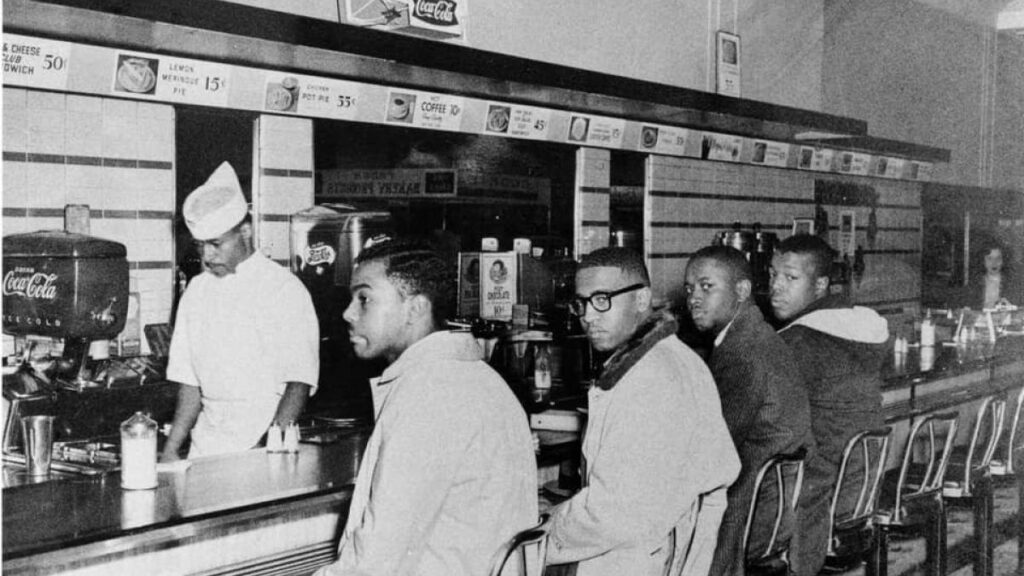

The Tactics of Dissent: Understanding Different Types of Protest

Bass & Beyond

Coastal Connections: Charlotta Bass, Martin Luther King, and Cesar Chavez

Bass & Beyond

Charlotta Bass and the Zoot Suit Riots: A Voice Emerges for Justice

News & Updates

Looking Back: Our Spring Fellows Reflect on Brittney Griner’s Visit

Social Justice

Diversity In Children’s Entertainment: Then vs. Now

Education

Amplifying Voices and Correcting the Record

News & Lab Updates

Happenings in and around the Bass Lab

Art & Culture

Ava DuVernay: From Origin to Onward

Education

The Content Creator as Educator: How Scholars Are Turning Streams into Classrooms

Bass Fellow Spotlight

Meet Rafiq Taylor, The Fellow Turned PR Pro Bringing a Creator’s Perspective to Bass Lab

Third Reconstruction

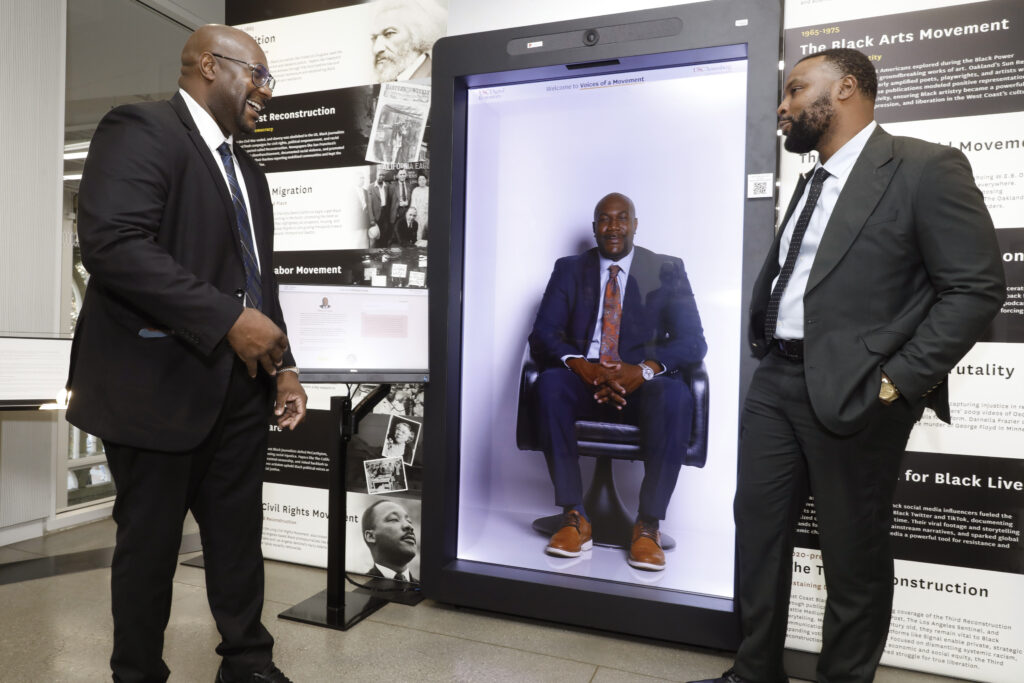

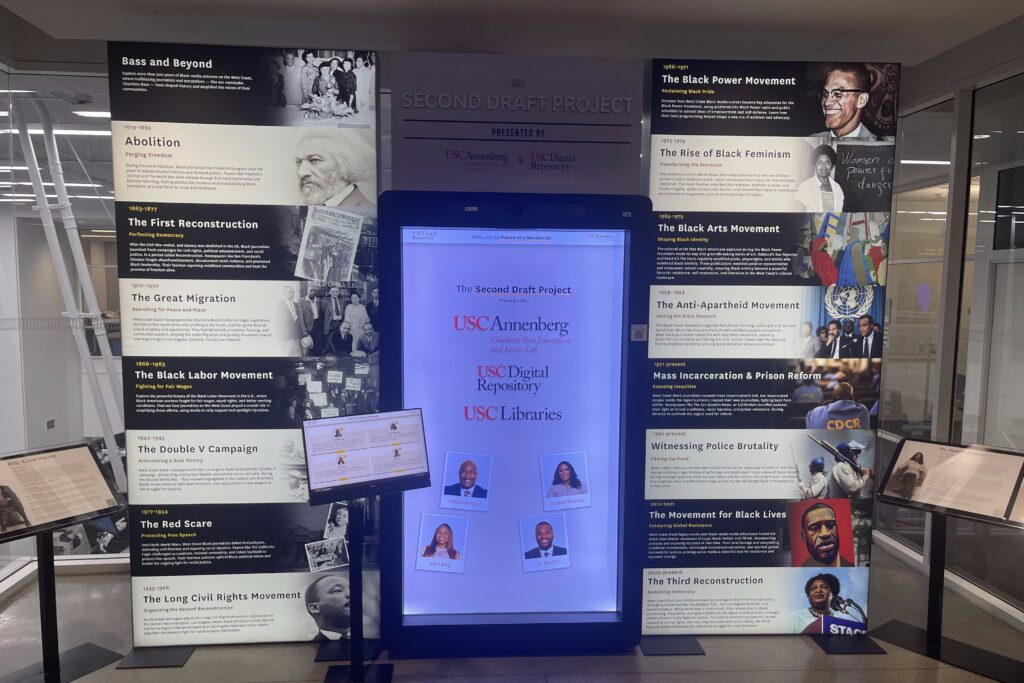

The Role of the Second Draft Project in Historical Documentation

Third Reconstruction

Engaging with the Second Draft Project’s AI-Powered Interviews

Education