TOP STORIES

From the Archives

Exploring how yesterday’s history shapes today’s headlines

Social Justice

Who’s Really Being Targeted by Blanket Deportation?

Opinion

Pain is Not a Right of Passage

Black Power Movement

Partners in Protest: The Brown Berets and the Black Panther Party

Bass & Beyond

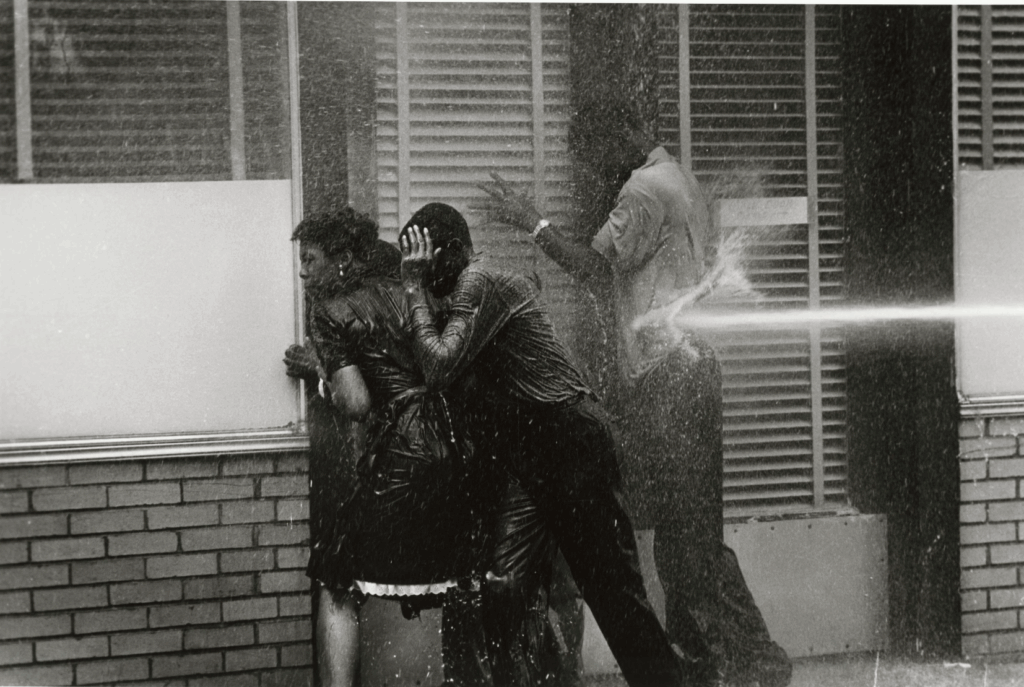

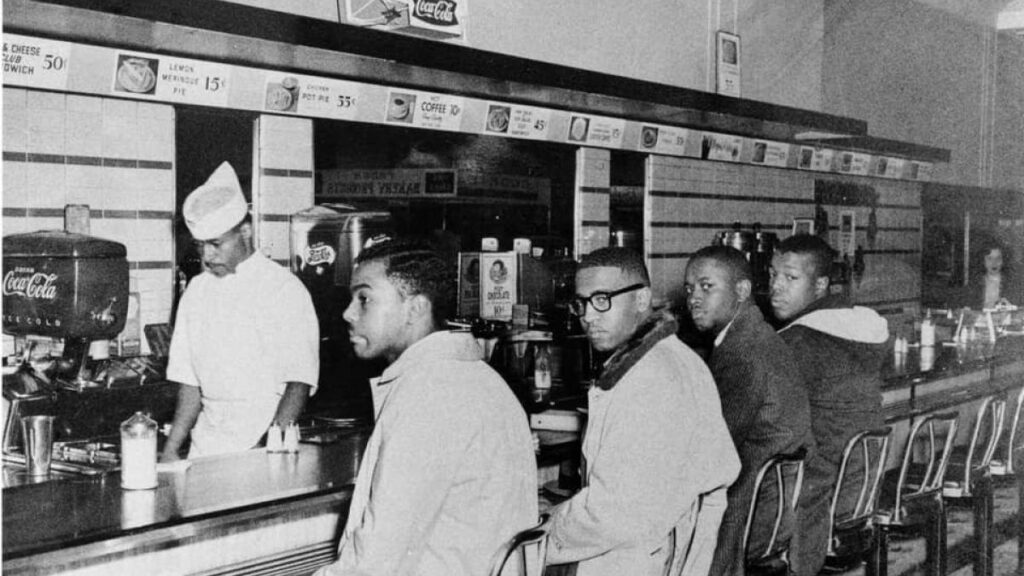

The Tactics of Dissent: Understanding Different Types of Protest

Bass & Beyond

Coastal Connections: Charlotta Bass, Martin Luther King, and Cesar Chavez

Bass & Beyond

Charlotta Bass and the Zoot Suit Riots: A Voice Emerges for Justice

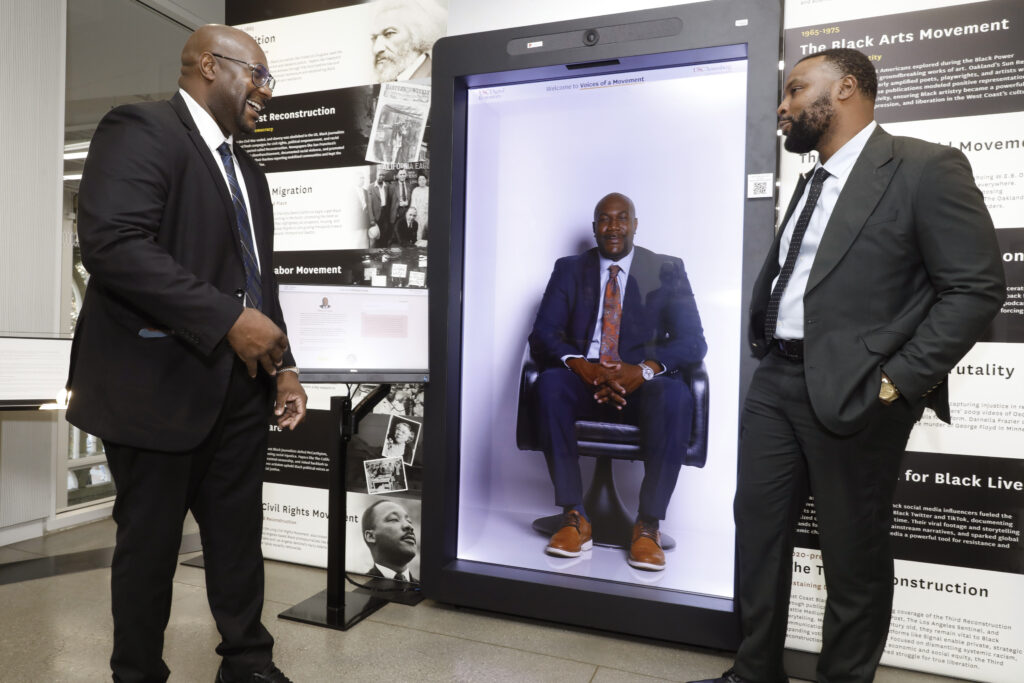

News & Lab Updates

Happenings in and around the Bass Lab

Social Justice

A Legacy of Resistance: Black Athletes and the Backlash to Protest

Social Justice

Sociologist Brittany Freidman Challenged Mass incarceration in “Carceral Apartheid”

News & Updates

“We’re All Connected”: Filmmaker Tevin Tavares on Community, Authenticity, and Storytelling

Site Visits

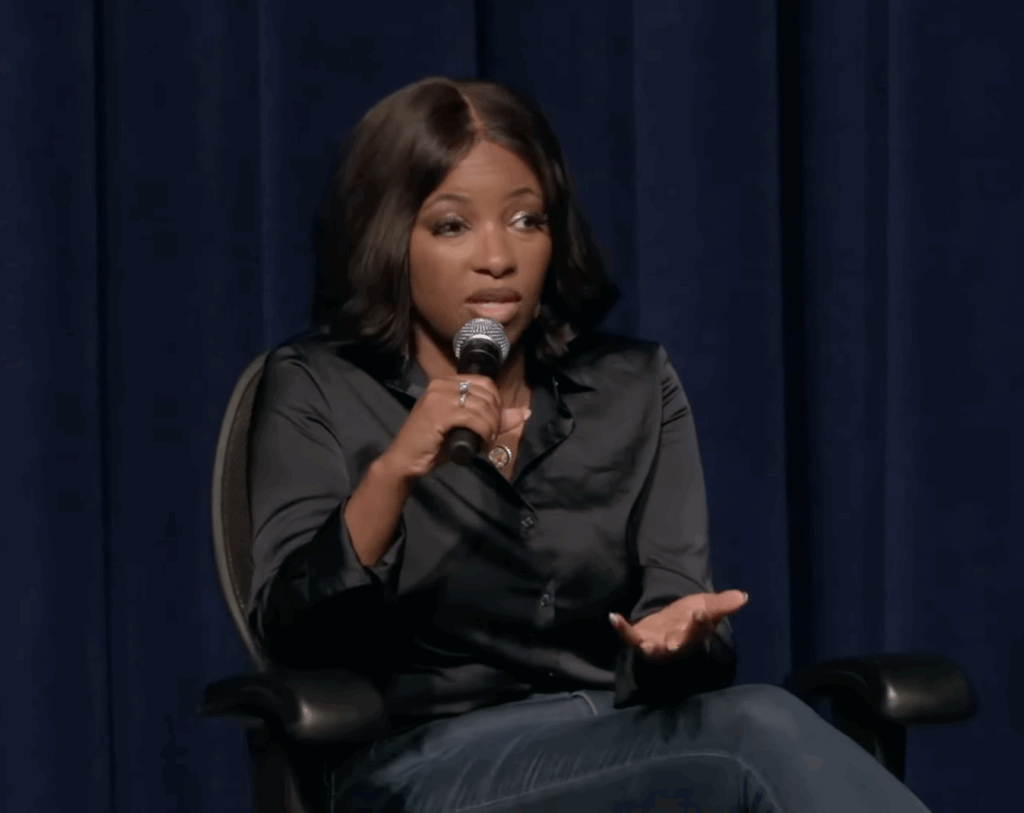

Rep. Jasmine Crockett and Bryan Tyler Cohen Discuss the Battle for American Democracy

Social Justice

Is Protest a Demand or a Warning? Recasting Demonstrations as Signals of Imminent Rupture

Education