TOP STORIES

From the Archives

Exploring how yesterday’s history shapes today’s headlines

Social Justice

Diversity In Children’s Entertainment: Then vs. Now

Education

Amplifying Voices and Correcting the Record

Third Reconstruction

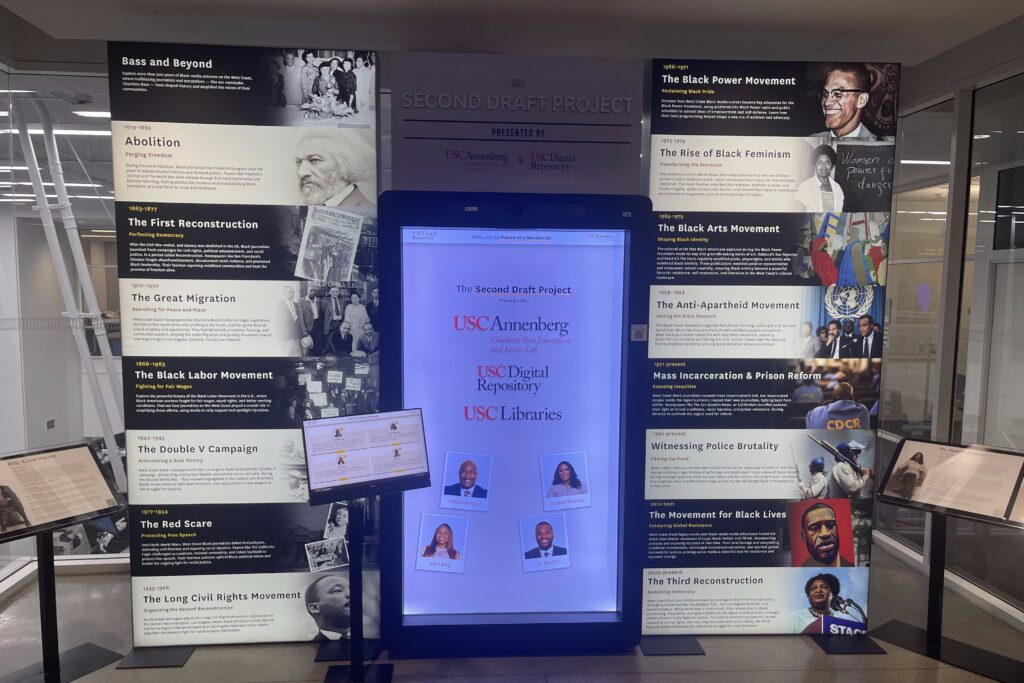

The Role of the Second Draft Project in Historical Documentation

Bass & Beyond

Black Oregonians & Public Television Role in the Social Justice Movement

Third Reconstruction

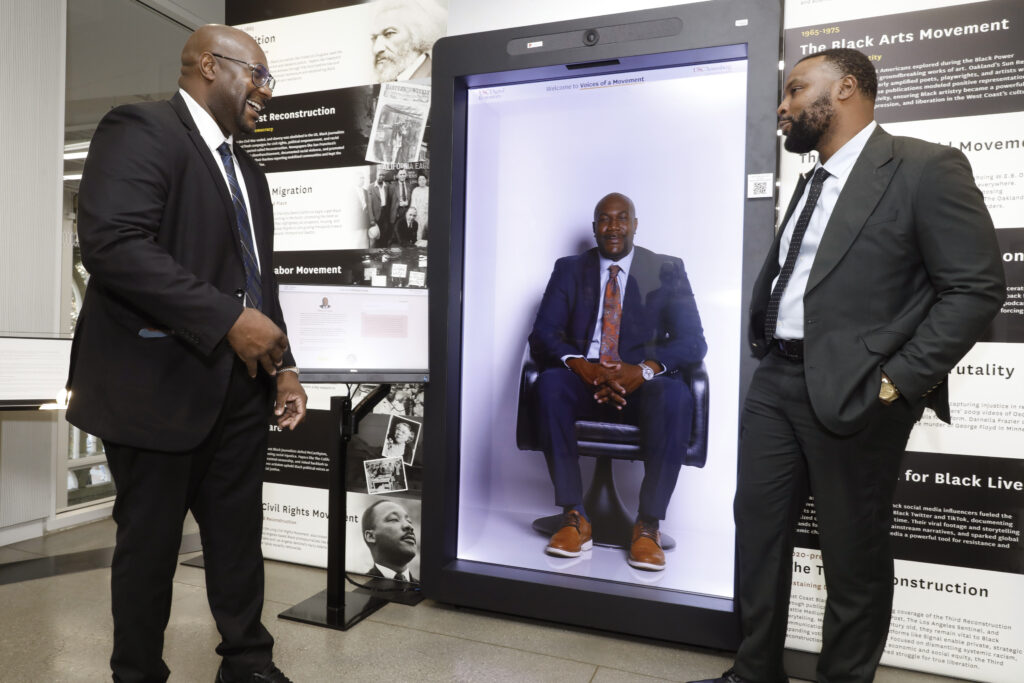

Engaging with the Second Draft Project’s AI-Powered Interviews

Bass & Beyond

West Coast Connections: Charlotta Bass x Dr. King

News & Lab Updates

Happenings in and around the Bass Lab

News & Updates

Looking Back: Our Spring Fellows Reflect on Brittney Griner’s Visit

Bass Fellow Spotlight

Meet Rafiq Taylor, The Fellow Turned PR Pro Bringing a Creator’s Perspective to Bass Lab

Education

How Black Washingtonians Used Public TV to Report on Social Justice Issues

Partner Spotlight

A Partnership with the USC Digital Repository: Using Advanced Tech to Bring People Closer

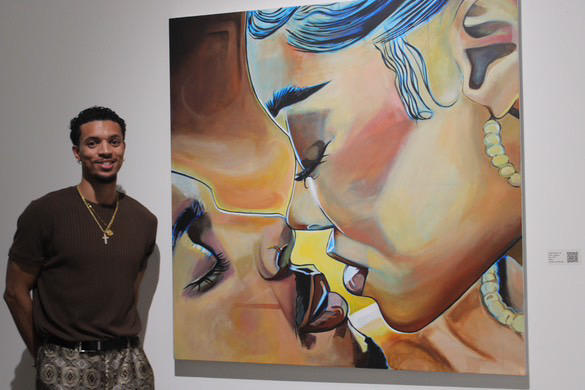

Art & Culture

The Road to Abbott Elementary

Partner Spotlight